Visible Speech: The System of Phonetic Symbols Developed by Alexander Melville Bell

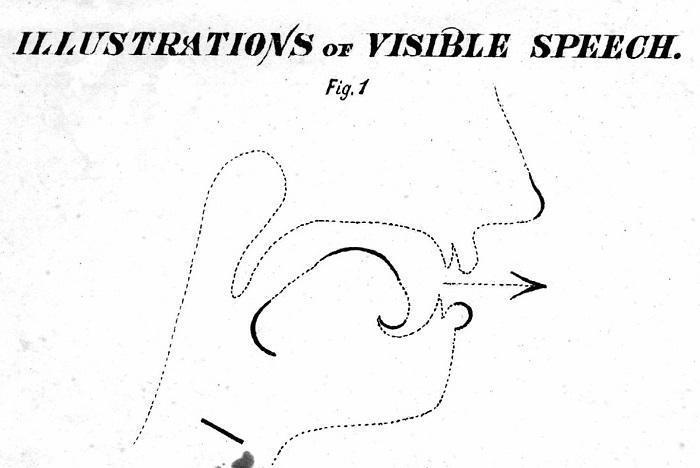

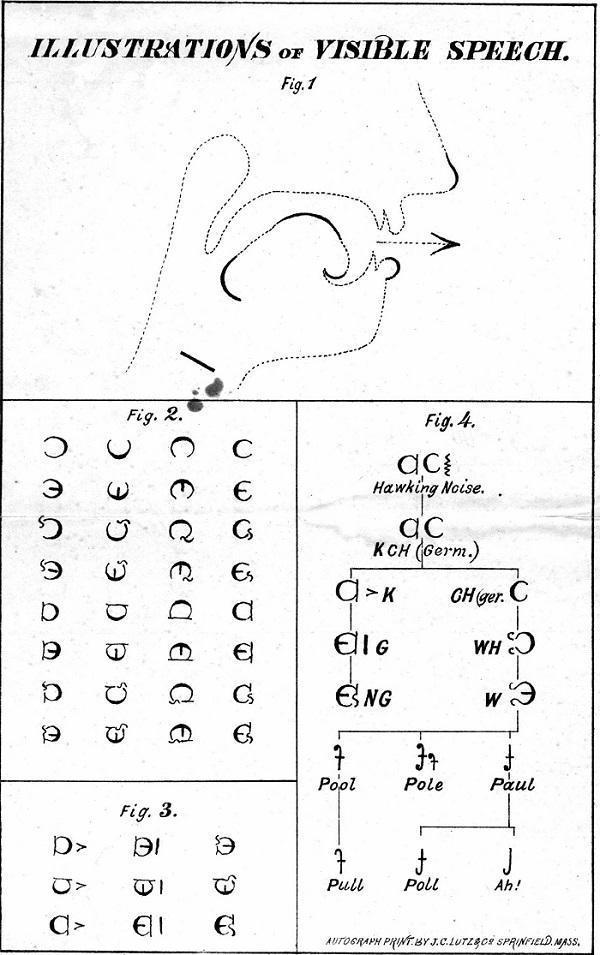

Visible Speech is a phonetic system of symbols that was created by Alexander Melville Bell in 1867 to represent the position of speech organs in articulating sounds. Bell was an internationally renowned linguist and author of books on the subject of proper elocution, and the system was intended to aid the deaf in learning to speak. It consists of symbols that show the movement and position of the throat, tongue, and lips as they produce language sounds. Visible Speech is a type of phonetic notation and was used to represent regional accents with high accuracy.

In 1864, Bell published his first works on Visible Speech to help the deaf learn and improve their pronunciation. He created two written short forms using his system of 29 modifiers and tones, 52 consonants, 36 vowels, and a dozen diphthongs. These two forms were named World English and Line Writing, with the former being similar to the International Phonetic Alphabet. The system was promoted as having numerous applications, including its worldwide use as a universal language.

Bell’s son, Alexander Graham Bell, learned the symbols, assisted his father in public demonstrations of the system, and later improved on his father’s work. Alexander Graham Bell became a powerful advocate of visible speech and oralism in the United States, and the money he earned from his patents helped him pursue this mission.

Melville Bell’s Visible Speech book, published in 1867, contained information about the system of symbols he created. When used to write words, the symbols indicated pronunciation so accurately that they could reflect regional accents. In demonstrations, Melville Bell employed his son, Alexander Graham Bell, to read from the visible speech transcript of the volunteer’s spoken words. The audience would be astounded when he said the words back exactly as the volunteer had spoken them.

Melville Bell’s system was useful not only because its visual representation mimicked the physical act of speaking, but also because it could be used to write words in any language, hence the name “Universal Alphabetics.” However, it was found to be cumbersome and thus a hindrance to the teaching of speech to the deaf, compared to other methods. After a dozen years or so in which it was applied to the education of the deaf, Visible Speech faded from use.

Alexander Graham Bell later devised another system of visual cues that also came to be known as visible speech, but it did not use symbols written on paper to teach deaf people how to pronounce words. Instead, his system involved the use of a spectrogram, a device that makes “visible records of the frequency, intensity, and time analysis of short samples of speech.” The spectrogram translated sounds into readable patterns via a photographic process, and modern implementations of Bell’s idea are used in phonology, speech therapy, and computer speech recognition.

The idea of using a spectrograph to translate speech into a visual representation (a spectrogram) was created in the hopes of enabling the deaf to use a telephone. If the sounds could be translated into something readable, then a deaf person at the receiving end could then read out the pattern of speech to determine its meaning without having to hear what was said. The spectrograph readings could also be used to teach pronunciation by having a person speak into the spectrograph and watch a small television-like screen to monitor the precision of their utterances.

Visible Speech, in its different forms, was a significant development in the study of linguistics and speech therapy, and it was instrumental in aiding the deaf in learning to speak. It remains an important part of the history of phonetics and has contributed to modern research in speech technology.