Gordon revolutionized the concept of epidemiology, introducing it as a fundamental basis for accident prevention. The idea that accidents were just random occurrences with no way to predict or prevent them was prevalent in the early 1900s; however, Gordon saw potential in applying the same principles used to study diseases and illnesses when studying accidents instead. He believed there could be an understanding gained by this approach which enabled effective preventive action going forward.

Gordon took a comprehensive and holistic approach to accident prevention, recognizing that accidents are the product of an array of elements such as individual traits, environmental circumstances, and social/organizational norms. By investigating these components and their collective effect on safety incidents, Gordon hoped to distinguish patterns in injury statistics and devise solutions for averting them.

Gordon decided to put his hypothesis to the test and conducted a series of studies that examined what caused accidents in places such as factories, mines, and hospitals. The results proved Gordon’s theory correct – these unfortunate events weren’t happenstance but rather the consequence of particular sets of conditions that could be identified and taken care of.

Drawing on these insights, Gordon constructed an accident prevention model that concentrated on recognizing and handling the root causes of accidents. This new model highlighted how critical it is to assess mishaps in their particular settings rather than just as individual incidents, calling for tailored approaches that consider all relevant factors of each event.

Gordon’s work was revolutionary, with far-reaching implications for accident prevention. By studying and preventing accidents in this way, he provided a new framework that could be used to create strategies and interventions designed to tackle existing issues proactively instead of utilizing reactive measures only. As such, Gordon shifted the entire focus of accident prevention from merely reacting after an incident to actively seeking out root causes before they become problems.

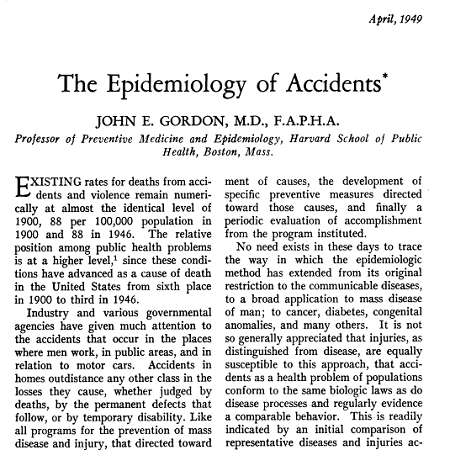

Epidemiology of Accidents

Excerpt from Gordon’s Article

Reference URL:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1528041/pdf/amjphnation01032-0075.pdf

EXISTING rates for deaths from accidents and violence remain numerically at almost the identical level of 1900, 88 per 100,000 population in 1900 and 88 in 1946. The relative position among public health problems is at a higher level,’ since these conditions have advanced as a cause of death in the United States from sixth place in 1900 to third in 1946. Industry and various governmental agencies have given much attention to the accidents that occur in the places where men work, in public areas, and in relation to motor cars. Accidents in homes outdistance any other class in the losses they cause, whether judged by deaths, by the permanent defects that follow, or by temporary disability. Like all programs for the prevention of mass disease and injury, that directed toward accidents is necessarily a team effort involving a number of agencies and a variety of disciplines. Although health departments have an obligation in all accident prevention, a better record for home accidents is believed to depend largely upon what health departments do in that field. If home accidents are primarily a public health problem, then that problem is reasonably to be approached in the manner and through the techniques that have proved useful for other mass disease problems. This includes first an epidemiologic analysis of the particular situation, an establishment of causes, the development of specific preventive measures directed toward those causes, and finally a periodic evaluation of accomplishment

from the program instituted.

No need exists in these days to trace the way in which the epidemiologic method has extended from its original restriction to the communicable diseases, to a broad application to mass disease of man; to cancer, diabetes, congenital anomalies, and many others. It is not so generally appreciated that injuries, as distinguished from disease, are equally susceptible to this approach, that accidents as a health problem of populations conform to the same biologic laws as do disease processes and regularly evidence a comparable behavior. This is readily indicated by an initial comparison of representative diseases and injuries according to frequency distributions in time, an epidemiologic characteristic of established value in separating one mass disease from another, and in distinguishing kinds of behavior: