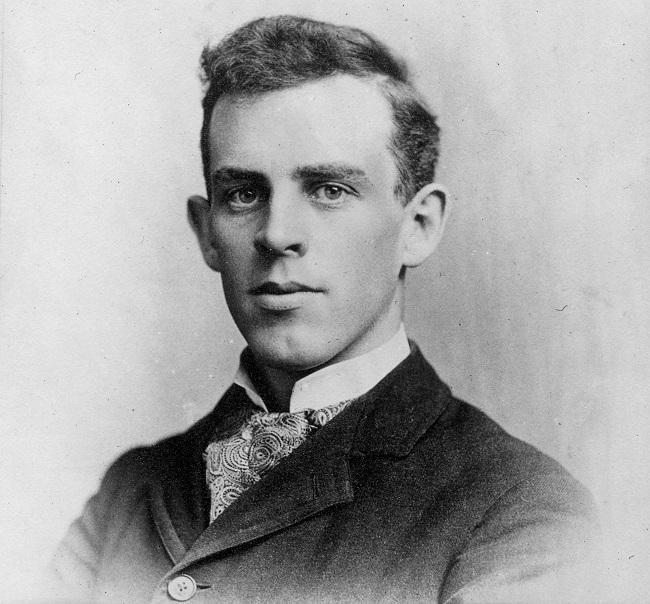

David Grandison Fairchild was an American botanist and plant explorer who introduced over 200,000 exotic plants and crop varieties into the United States, including soybeans, pistachios, mangos, nectarines, dates, bamboos, and flowering cherries. Born in 1869 in Lansing, Michigan, Fairchild grew up in Manhattan, Kansas, and attended the Kansas State College of Agriculture, where his father was president. After completing his education, Fairchild joined the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and became a plant explorer, travelling around the world in search of plants of economic and aesthetic value that could be cultivated in the US.

During his explorations, Fairchild became passionate about tropical horticulture, an interest he pursued throughout his life. He helped organize the USDA’s Office of Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction, and from 1904 to 1928, served as its Chairman, introducing many new kinds of plants to the US. One of his accomplishments was introducing cherry trees from Japan to Washington, DC, and he is also credited with introducing kale, quinoa, and avocados to Americans. In 1898, he established the introduction garden for tropical plants in Miami, Florida, and he built a home on an 8-acre parcel on Biscayne Bay in Coconut Grove, Florida, which he named “The Kampong.” He covered this property with an extraordinary collection of rare tropical trees and plants and eventually wrote a book about the place, entitled The World Grows Round My Door.

Fairchild also played an important role in introducing cotton to the southwestern United States. At the time, the US led the world in cotton production, but the southwestern United States did not produce commercial quantities of cotton. Fairchild visited Egypt in 1902 and brought back a few cultivars that could thrive under irrigation in the deserts of the southwestern United States. A USDA team led by Thomas H. Kearney selected among these cultivars, and after a decade of refinement, released the first cultivar successful in the southwestern United States. This particularly high-quality cotton eventually came to be known as Pima.

As a nation, the United States had long struggled to define its cuisine in the century following its establishment. Meat, potatoes, and cheese dominated American diets, with fruits and vegetables rarely making an appearance on dinner plates. Moreover, the widely held belief at the time was that consuming too many spices or condiments could compromise one’s moral character, while plain, flavorless foods like graham crackers were seen as a cure for sexual urges. However, in the 1870s, a shift towards seasoning and nutrition education began to take hold, as Americans became more willing to try new foods and new ways of preparing traditional dishes.

This growing interest in food proved the perfect opportunity for adventurer-botanist David Fairchild, who lived during this period of expanding gastronomic interest. In the 1890s, Fairchild began working for the United States Department of Agriculture, traveling the world to gather and send back seeds or cuttings of over 200,000 kinds of fruits, vegetables, and grains. His department, the Office of Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction, researched and distributed new crops to farmers around the United States.

David Fairchild’s missions were not without risk, as he was sometimes forced to steal exotic crops that other countries sought to protect. For example, while in Bavaria, Fairchild acquired some of the best hops in the world, which he brought back to the United States, thus revolutionizing the hops industry in America. Similarly, Fairchild played a pivotal role in the planting of Japanese Cherry Blossom trees in the nation’s capital.

Despite the risks and challenges he faced, Fairchild’s efforts proved successful, as he helped establish a tradition of food exploration that inspired other explorers to follow in his footsteps. However, the program he pioneered came to an end with the passing of a quarantine law after World War I that required all plants coming into the United States to be searched and tested before they could be distributed.

Although the process of introducing new crops to American farmers was difficult, Fairchild’s contributions to the nation’s agriculture and culinary scenes cannot be overstated. The American diet would look vastly different today if not for his tireless efforts to bring exotic crops from around the world to American soil. His favorite discovery, the mangosteen, never quite caught on in the United States due to the fruit’s limited growing conditions and high labor costs, but Fairchild remained convinced that it was the best fruit in the world.

David Fairchild wrote four books that describe his extensive world travels and his work introducing new plant species to the United States. Beside sharing his legendary tropical botanical expertise, Fairchild provided graphic accounts of native cultures he was able to see before their modernization. He was an accomplished photographer and illustrated these books himself. The World Was My Garden won a National Book Award as the Bookseller Discovery of 1938, voted by members of the American Booksellers Association.

Fairchild married Marian Bell, the younger daughter of Alexander Graham Bell, in 1905. They had two children, Alexander Graham Bell Fairchild and Nancy Bell. Fairchild was a member of the board of trustees of the National Geographic Society and an officer in what is now called the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing. He was also a member of the board of regents of the University of Miami from 1929 to 1933, and for three of those years, he was chairman of the board.

David Fairchild’s relationship with Marian Bell was an important factor in his career. Marian Bell was the daughter of Alexander Graham Bell, the inventor of the telephone, and she and Fairchild were married in 1905. Her family connections and wealth helped support Fairchild’s work and gave him access to influential people in government and society. Marian Bell was a close friend of Eliza Scidmore, who was instrumental in the planting of Japanese cherry blossom trees in Washington D.C. through her efforts with the National Geographic Society. Marian used her influence with her husband and his connections to help support Scidmore’s work, which helped solidify Fairchild’s reputation as an expert in plant exploration and introduction. They acted as a team, and Marian accompanied Fairchild on some of his expeditions, including trips to the Philippines and China. She helped document their travels and assisted in the collection and preservation of plant specimens. Furthermore, her contributions to her husband’s books, particularly his memoir “The World Was My Garden,” were invaluable in capturing the essence of their shared experiences. Additionally, her fluency in several languages, including Spanish and French, proved useful in their travels to foreign countries. Marian Bell was a supportive and influential partner who helped to advance Fairchild’s career and played an important role in his success as a botanist and explorer.

Fairchild died on August 6, 1954, in Coconut Grove, Florida. He oversaw the introduction of more than 200,000 exotic plants, crop varieties, species, and varieties of plants into the United States, among them the flowering cherry, Chinese soybean, pistachios, nectarines, bamboo, avocados, East Indian mangoes, and horseradish. He also wrote several books, including Exploring for Plants, and the autobiographical The World Was My Garden. Fairchild’s work played a significant role in shifting America towards seasoning and cultivating a better understanding of nutrition, introducing the exotic foods that we now take for granted in the American diet.

References: