Vermiculite is a fascinating mineral that expands when heated rapidly. This expanded form is used in various applications such as construction and consumer materials, agricultural and horticultural products, and industrial products. It’s been a commercial commodity for over 50 years and is utilized across the globe.

Unfortunately, vermiculite ore from the Libby mine in Montana, which was responsible for more than half of the worldwide production from 1925 to 1990, was contaminated with asbestos and asbestos-like fibers. This led to severe health issues for local miners, millers, and some downstream workers. Mining ceased at the Libby mine in 1990, but health concerns persist regarding asbestos-contaminated vermiculite, particularly when used as loose-fill insulation in buildings.

As for uncontaminated vermiculite, there is no solid evidence that its dust causes serious health issues. However, workers should still avoid prolonged, high-level exposure to any dust. It’s important to note that the health problems associated with asbestos-contaminated vermiculite are due to the contaminant fibers rather than the vermiculite itself.

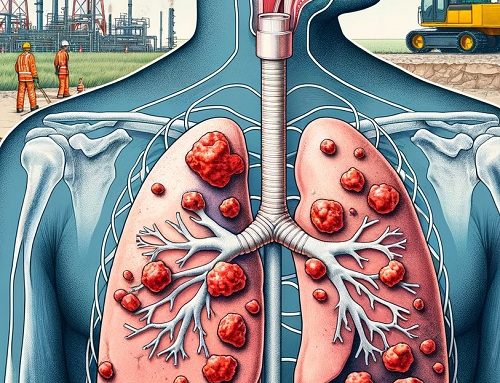

Asbestos exposure can lead to severe health issues, including asbestosis (a scarring disease of the lung), pleuritis (inflammation of the chest cavity), lung cancer, and malignant mesothelioma (another type of cancer). The risk of these debilitating or fatal diseases generally increases with the intensity and duration of exposure. Smokers are at an increased risk of lung cancer from inhaling asbestos fibers. Most asbestos-related diseases take at least 15 years to manifest after initial exposure.

To protect workers from asbestos-contaminated vermiculite, any vermiculite from the Libby mine should be considered potentially contaminated. The only way to know the amount of asbestos in a material is to have it tested. Bulk sampling is reliable only when over 1% of the material is asbestos. Disturbing vermiculite with less than 1% asbestos can still result in hazardous concentrations of airborne asbestos fibers.

Workers should consult OSHA asbestos standards for general industry and construction when working with vermiculite known or presumed to be contaminated with asbestos. When handling asbestos-contaminated vermiculite, workers should follow NIOSH’s general guidelines for limiting exposure, such as avoiding disturbance, isolating work areas, using wet methods, and never using compressed air for cleaning.

Proper respiratory protection is crucial when working with vermiculite presumed to contain asbestos. Depending on airborne concentration or conditions of use, respirators equipped with high-efficiency filters or supplied air respirators should be utilized. Medical clearance and respirator training are also required. Disposable respirators or dust masks are not suitable for avoiding asbestos exposure.

Workers who have had significant exposure to vermiculite from Libby or other asbestos-contaminated materials should consider a medical exam from a physician knowledgeable about asbestos-related diseases. Employers can help by offering smoking cessation programs for workers who smoke.

NIOSH is actively involved in research and prevention activities related to asbestos-contaminated vermiculite. They are evaluating the potential for asbestos exposure from other sources and updating a study on vermiculite workers from the 1980s, which found significant excesses of asbestosis and lung cancer related to contaminant fiber exposures.

Furthermore, NIOSH is providing technical assistance to the EPA and ATSDR, the lead federal agencies addressing current concerns about community health risks associated with asbestos-contaminated vermiculite from Libby.

While more information is being gathered, workers should take precautions to minimize the generation and inhalation of dust when handling vermiculite known or presumed to be contaminated by asbestos. It’s crucial to avoid prolonged high-level exposures to any dust. Employers have a responsibility to ensure that their employees are educated about the potential risks of working with vermiculite and are provided with the necessary protective equipment and training to minimize those risks.

Homeowners and building managers should also be aware of the potential risks associated with asbestos-contaminated vermiculite, particularly if it has been used as loose-fill insulation. If you suspect your home or building may contain vermiculite insulation from the Libby mine, it’s essential to consult with a professional asbestos abatement company before attempting any renovations or removal.

When it comes to the disposal of waste and debris contaminated with asbestos, it’s essential to follow OSHA and EPA guidelines. This typically involves using leak-tight containers and proper disposal methods to prevent the spread of asbestos fibers.

As for the future of vermiculite, new sources and suppliers are being sought out to ensure the continued availability of this valuable mineral for various industries. These sources must adhere to strict regulations and testing to guarantee that they do not pose the same health risks as those associated with the Libby mine.

Innovations in technology and increased awareness surrounding the potential dangers of asbestos-contaminated vermiculite have led to improved safety measures for workers and communities. By staying informed and following guidelines set forth by regulatory agencies, we can mitigate the risks associated with vermiculite and continue to benefit from its many versatile uses.

Vermiculite is an incredibly useful and versatile mineral with a wide range of applications. However, its past association with asbestos contamination and the subsequent health risks have raised concerns and necessitated caution in its handling and use. By understanding the risks, adhering to guidelines, and staying informed about new developments in vermiculite research and safety, we can continue to utilize this valuable resource while minimizing potential hazards.

The Controversy over the Vermiculite from the Libby Mine

The history of vermiculite is one of both utility and controversy. Vermiculite, a naturally occurring mineral with unique properties, has been used in various applications for over a century. However, it was not until the 1920s that vermiculite mining began in earnest in Libby, Montana. This mine, which would go on to supply a significant portion of the world’s vermiculite, was later discovered to have a dark secret lurking beneath its surface.

The Libby mine produced vermiculite under the commercial name Zonolite, which was eventually acquired by W. R. Grace and Company in 1963. Unfortunately, the vermiculite extracted from the mine was heavily contaminated with asbestos, a hazardous material that posed serious health risks. Despite this contamination, mining operations at the Libby site continued until 1990, with little regard for the well-being of the miners and local residents.

The consequences of this asbestos contamination have been far-reaching and devastating. Over 35 million homes in the United States are estimated to have used vermiculite, and many of these homes may still contain asbestos-laden insulation. The potential health risks associated with exposure to asbestos have left homeowners and building managers with difficult decisions to make regarding the removal of vermiculite insulation.

In 2006, an article published in The Salt Lake Tribune brought the health risks associated with asbestos-contaminated vermiculite to the forefront of public consciousness. The article accused W. R. Grace and Company of covering up the dangers posed by their Zonolite product and revealed that several sites in the Salt Lake Valley had been remediated by the EPA due to asbestos contamination.

The legacy of the Libby mine continues to haunt the town to this day. Over 400 people have died from asbestos-related diseases, and many more suffer from ongoing health problems. In 1999, a Seattle Post-Intelligencer story prompted the EPA to make the cleanup of Libby a priority. It has since been called the worst case of community-wide exposure to a toxic substance in U.S. history.

Since then, the EPA has spent $120 million in Superfund money to clean up the site, and W. R. Grace and Company has faced numerous legal challenges, including a rejected appeal to the Supreme Court over $54.5 million in fines levied against them. In 2009, several former executives and managers of the mine were indicted on criminal charges for allegedly disregarding and covering up health risks to employees.

The case ended in acquittals, but the impact of the asbestos contamination continues to be felt by the residents of Libby. As of the indictment date, approximately 1,200 residents had been identified as suffering from some form of asbestos-related abnormality.

In response to the ongoing public health crisis, the EPA issued a public health emergency in and near Libby in 2009. This declaration allowed federal agencies to provide funding for health care and the removal of contaminated insulation from affected homes.

The history of vermiculite is a cautionary tale of the consequences of putting profits before people. While the mineral itself has many beneficial applications, the actions of W. R. Grace and Company and the mining industry at large have left a lasting stain on the communities affected by asbestos-contaminated vermiculite.

Today, vermiculite mines around the world are regularly tested for asbestos to ensure that their products are safe for use. However, the legacy of the Libby mine serves as a stark reminder of the importance of vigilance and transparency in the mining industry, as well as the responsibility of corporations to prioritize the health and safety of the communities they impact.

The story of vermiculite is a complex one, combining the potential benefits of a versatile and useful mineral with the devastating consequences of corporate negligence and environmental contamination. The history of vermiculite mining, particularly in Libby, Montana, underscores the critical importance of transparency, regulation, and corporate responsibility in the face of potential health hazards.

As we move forward, it is essential that we learn from the mistakes of the past and strive to create a safer and more sustainable mining industry. This means implementing rigorous safety standards, conducting regular testing for contaminants such as asbestos, and ensuring that companies are held accountable for their actions.

It is crucial to provide support for the communities that have been affected by asbestos-contaminated vermiculite. The public health emergency declared in and around Libby has enabled federal agencies to allocate funding for health care and the removal of hazardous materials from homes. These efforts must continue, as the long-term effects of asbestos exposure remain a serious concern for many residents.

In addition to addressing the existing consequences of vermiculite mining, we must also work to prevent future disasters. This requires not only improved safety measures within the industry but also a greater emphasis on research and development of alternative materials that can provide the same benefits as vermiculite without the associated risks.

References: