In 1907, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania became the epicenter of the country’s first significant survey of industrial life. The Russell Sage Foundation sponsored the work of approximately 70 investigators including young lawyer Crystal Eastman, artist Joseph Stella, and photographer Lewis Hine. They researched, interviewed, and depicted the industrial and social conditions of Pittsburgh. The largest undertaking of its kind, the results, known as the Pittsburgh Survey, contributed to the creation of the social survey movement and the passage of new worker’s compensation laws. The research was first published in magazines, including Collier’s, in 1908 & 1909, then was expanded into a series of six books published from 1909 to 1914. Used by progressive lawmakers in promoting social reforms throughout the nation, the Pittsburgh Survey served as a model for sociological research and inspired a multitude of other surveys, more than 2,500 of which were performed nationwide over the next two decades.

The idea was influenced by Progressive Era activism and originated with Alice B. Montgomery, the chief probation officer of the Allegheny Juvenile Court, who proposed the survey after reading about a social study of Washington, D.C. With the support of a small group of Pittsburgh businessmen and welfare officials, set the project in motion. Headed by Paul U. Kellogg, the investigators descended on Pittsburgh in the fall of 1907 to examine the quintessential industrialized American city.

The Russell Sage Foundation, which operates to this day, is an American non-profit organization established by Margaret Olivia Sage in 1907 for “the improvement of social and living conditions in the United States.” It was named after her recently deceased husband, railroad executive Russell Sage. The foundation dedicates itself to strengthening the methods, data, and theoretical core of the social sciences to better understand societal problems and develop informed responses. It supports visiting scholars in residence and publishes books and a journal. It also funds researchers at other institutions and supports programs intended to develop new generations of social scientists. The foundation focuses on labor markets, immigration and ethnicity, and social inequality in the United States, as well as behavioral economics.

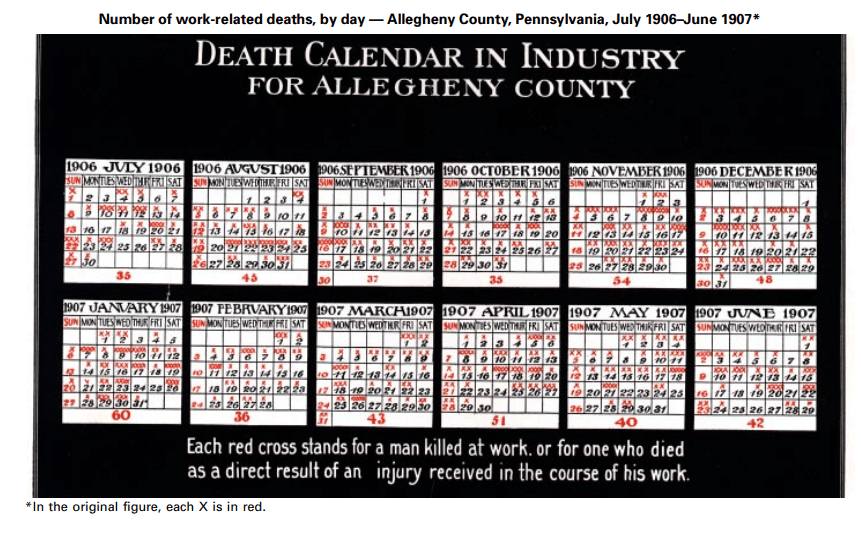

Crystal Eastman, through the record-keeping, noted on the death calendar (see image above), found that 526 people died at work and thousands suffered injuries in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania from 1906 to 1907. 195 of the 526 people who died were steelworkers. In contrast, in 1997, 17 steelworker fatalities occurred nationwide.

The National Safety Council once estimated that in 1912, 18,000–21,000 workers died from work-related injuries. In 1913, the Bureau of Labor Statistics documented approximately 23,000 industrial deaths among a workforce of 38 million, equivalent to a rate of 61 deaths per 100,000 workers. Under a different reporting system, data from the National Safety Council from 1933 through 1997 indicate that deaths from unintentional work-related injuries declined 90%, from 37 per 100,000 workers to 4 per 100,000. The corresponding annual number of deaths decreased from 14,500 to 5100; during this same period, the workforce more than tripled, from 39 million to approximately 130 million.

Overview of the Six Volumes of the Survey

The Pittsburg Survey, Volume I – Women and the Trades

Volume I of the survey, headed by Elizabeth Beardsley Butler, examined the livelihood of Pittsburgh’s women workers. A 1905 graduate of Barnard College, Butler became a sociologist focusing on women and child laborers. In this volume of the study, she analyzed the working women, and her analysis pointed to the horrible living conditions at home and in the workplace. Ironically, while on this survey, Butler contracted tuberculosis, of which she died in 1911.

The Pittsburgh Survey, Volume II – Work Accidents and the Law

Volume II of the survey related to the work injuries and the legal recompense that workers were offered. Compiled by Crystal Eastman, a New York University-educated lawyer, suffragist, and future founder of the American Civil Liberties Union, charted and illustrated a rise in workplace injuries in the steel industry. Also, the survey pointed out that workers had very little compensation for their injuries, especially in the steel manufactory. Her work also sponsored the first workers’ compensation law in the nation.

The Pittsburgh Survey, Volume III – The Steel Workers

Volume III, arguably the most comprehensive volume of the series, focused on the steelworkers of Pittsburgh. The compiler, John A. Fitch, a University of Wisconsin graduate student, followed professor John R. Commons when the latter was invited to help with the survey. Fitch interviewed many steelworkers about their lives and work. Photographer Lewis Hines and artist Joseph Stella complimented his work with images of these individuals, some of the best depictions of life in the industry available.

The Pittsburgh Survey, Volume IV – Homestead: The Houses of a Mill Town

Volume IV, produced by Margaret F. Byington, studied the actual lives of people in the Homestead Mill town. The first half of the study focused on the English-speaking population of the town, and the second on the “slavs” as Byington referred to them. One of her most striking sections is titled “On $1.65 a day” and describes the livelihood of an entire family with only that amount to spend per day. Included are several wonderful photographs of the village itself.

The Pittsburgh Survey, Volume V and VI – The Pittsburgh District Civic Frontage

These two volumes, compiled by Paul Kellogg, the head of the survey, were a collection of essays on the city. Complete with numerous photographs, both pieces fleshed out the remainder of the work, demonstrating the environmental effect of the steel industry as well as the overall image of the working man. Kellogg, an eminent social reformer, later headed the American Foreign Policy Association and led an effort in 1915 alongside Henry Ford to end the First World War. He spent the remainder of his life trying to aid the underprivileged and tell their story as he had done in The Pittsburgh Survey.