Pennsylvania’s first mine safety law was passed by the state legislature in April 1869.

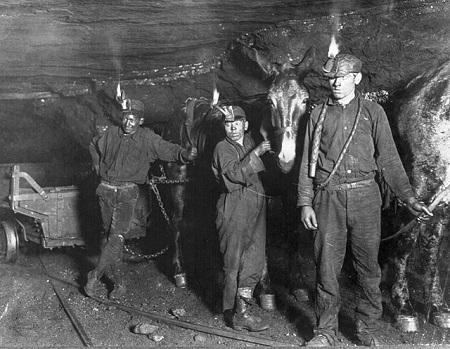

Mining coal came at an enormous human cost. Before 1870, the records are spotty, but gas explosions seem to have been common. A gigantic roof fall covering fifty acres killed fourteen men in a Carbondale, Pennsylvania mine in 1846, and haulage also took a regular toll. Beginning in 1870, the reports of Pennsylvania’s mine inspectors document the extraordinarily dangerous nature of anthracite mining. From 1870 to 1913, the fatality rate averaged 3.42 per thousand employees per year compared to 2.87 for Pennsylvania’s bituminous miners from 1877to 1913. And since far more men mined anthracite than bituminous coal during these years, hard coal mining typically killed over 400 men a year compared to “only” about 250 in Pennsylvania’s bituminous industry. In fact, in the years just before World War I, Pennsylvania anthracite accounted for a fifth of all coal mining fatalities nationwide. In 1916, the hard coal miners experienced a fatality rate that was 4.75 times greater than that in manufacturing. Among major occupational groups for which data are available, only railroad trainmen typically ran greater risks.

While Pennsylvania’s early mine laws are easy to criticize, they led to marked improvements in mine safety after 1870. The miners, aided from time to time by the mining press, had been petitioning the legislature for a safety code since the 1850s. In 1858, the Miners’ Journal reproduced a British mining law of 1855 and urged passage of a similar measure. That same year a bill calling for improved ventilation was submitted to the legislature, where it died – throttled, apparently by operator opposition. Finally, lobbying efforts by the miners’ union, the Workingmen’s Benevolent Association, paid off On April 12,1869, Pennsylvania became the first state to regulate mine safety. The law of 1869 applied only to anthracite mines in Schuylkill County. It established state mine inspection, and required that the inspector pass an examination on his qualifications.

The narrowly drafted 1869 law called “for the better regulation and ventilation of mines and for the protection of the miners” — but only in Schuylkill County. It outlined many requirements, including that mines possess ventilation in the form of furnaces or suction fans, that each mine employ a boss who would perform a safety inspection each morning before workers entered, and that systems be installed to enable communication between the mine and the surface. Under penalty of fine, it also prohibited mines from having workers ride to the surface in loaded cars and stipulated that the law would be enforced by newly designated inspectors authorized to enter and inspect the mines and machinery at “reasonable” times.

The 1869 law was partly a result of lobbying efforts organized by the WBA’s Committee on Political Action, according to a Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) account of the history of Irish workers in American mining. John Siney, the Irish immigrant founder of the WBA, became a miner after immigrating in 1863 to St. Clair, Pa., in Schuylkill County. There, he helped lead a six-week-long strike in 1868 that succeeded in preventing miners’ wages from being slashed for the second time in half a decade. He also led strikes to enforce state-legislated eight-hour work days.

The first federal mine safety statute wasn’t passed by Congress until 1891. It only applied to coal mines. (Noncoal mines weren’t regulated by such statutes until the passage of the Federal Metal and Nonmetallic Mine Safety Act of 1966.) The Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act — a more comprehensive law that covered both surface and underground mines, required inspections, increased enforcement power, set penalties for safety violations (including criminal penalties for willful violations), established health and safety standards, and provided compensation to miners who contracted black lung disease — was passed in 1969.

Beginning in 1870, the reports of Pennsylvania’s mine inspectors document the extraordinarily dangerous nature of anthracite mining. From 1870 to 1913, the fatality rate averaged 3.42 per thousand employees per year compared to 2.87 for Pennsylvania’s bituminous miners from 1877to 1913. And since far more men mined anthracite than bituminous coal during these years, hard coal mining typically killed over 400 men a year compared to “only” about 250 in Pennsylvania’s bituminous industry. In fact, in the years just before World War I, Pennsylvania anthracite accounted for a fifth of all coal mining fatalities nationwide. In 1916, the hard coal miners experienced a fatality rate that was 4.75 times greater than that in manufacturing. Among major occupational groups for which data are available, only railroad trainmen typically ran greater risks.