DISCOVERERS OF AMERICA – ANNUAL ADDRESS BY THE PRESIDENT – HON GARDINER GREENE HUBBARD

(Presented before the Society January 13, 1893)

This is Part 3 of 4.

Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4

Finally, they reached the Ladrone islands and found the food and rest they so much needed. They then sailed for the Philippine islands, where in a foolish affray with the natives, Magellan was killed; but he had finished his work—he had circumnavigated the globe; he had reached the east by sailing west. One of the three vessels which had crossed the Pacific was abandoned and burnt in the Philippine islands, another was lost in the Malaccas; the last, loaded with spice, returned to Spain and finished the most remarkable voyage on record. Of the 280 men who sailed with Magellan in September 1519, only 18 returned in September 1522. The cost of this fleet, with all its equipment, was about $20,000.00, less than one-half the cost of the steamer plying between Washington and Mount Vernon. The sale of the spices left a large profit to Charles V and the merchants who had furnished the funds for the adventure. The king of Spain gave to the heirs of Ferdinand Magellan for their coat of arms a terrestrial globe belted with the legend “Primus circumdedisti me”—”Thou first encompassed me.”

In 1513 Vasco Nunez Balboa, a Spaniard who had married an Indian princess, heard from the natives of the Pacific ocean and of the land of the Incas, where gold, silver, and precious stones abounded. On September 25, from the top of the mountains, he looked down on the Pacific ocean, the first European to behold it. He collected a few vessels on the Atlantic coast for a voyage of discovery to Peru, and, taking them to pieces, he carried them across the isthmus and launched them on the Pacific. Two thousand Indians, we are told, perished in this work. When nearly ready to sail, he was recalled by the governor of Darien and beheaded.

After the death of Balboa, Francisco Pizarro, one of his followers, returned to Spain with an account of the land of the Incas, and in 1529 was made governor and captain-general of this country, then called the province of New Castile, with leave to fit out at his own expense an expedition to conquer that territory. He left Panama with three ships, 180 men, and 27 horses, but it was not until two years later that they landed in Peru and began that contest which resulted in the overthrow of the Incas and in loading with riches the meanest of Pizarro’s followers. The civilization of the Incas, the highest type in America, was crushed.

The Spaniards soon after this conquest sailed still further southward, along the coast of Peru and Chile, even to the straits of Magellan.

Rumors of an Eldorado beyond the Andes came to Pizarro. One of his followers, Orellano, was sent to cross the Andes and descend to the headwaters of the Amazon, but he could not find the promised land. His party, famished and decimated by the fatigue of the journey and unable to return to the Pacific, built a boat and floated down the Amazon river 4,000 miles to its mouth.

Before the discovery of Peru by Pizarro, Sebastian Cabot, with a small Spanish fleet in 1527, sailed up the Rio de la Plata to the great falls of the Parana. He found some silver and gold mines in Brazil and heard of the civilization and riches of the Incas of Peru but was unable to cross the mountains to their country.

Thus within fifty years after the discovery of America, South America had been circumnavigated, its great rivers navigated, and the general features of the interior and its treasures of gold and silver made known to the Spaniards and Portuguese.

Some time before the conquest of Peru, the Spaniards heard rumors of the great city of the Montezumas. In March 1519, Hernando Cortez, one of the most daring and able of the adventurous Spaniards, landed on the coast of Mexico with ten vessels, 600 to 700 soldiers, 18 horsemen, and some cannon. He burnt his ships, thus cutting off all retreat, and then marched toward the city of Mexico. By his courage, address, and strategy, he conquered or made friends of several tribes of Indians hostile to Montezuma. He pushed onward to the city of Mexico, where he was received with great pomp by Montezuma and escorted into the city as his friend and guest.

Soon after Cortez, learning that Montezuma was preparing to attack the invaders, visited him in his palace and by persuasion and force took him to the Spanish quarters and kept him a prisoner. Some time later, the Indians chose another king and attacked the Spaniards, but after a slight success were defeated with great loss. Then Cortez, having captured and fortified the city of Mexico, defeated the other tribes and subdued the whole country. He subsequently explored it to the gulf of California and Lower California, on the other side of the gulf. He then returned to Spain but was not received by Charles V as he expected. Forcing his way to the royal presence, Cortez replied to Charles, who wished to know who the intruder was, “I am the man who has given you more provinces than your father left you cities.” There is no tale in the history of the world more marvelous than the conquest of Peru and Mexico when we consider the high culture and strength of the natives, the small number of Europeans engaged, the extent of the conquests, and the value of the treasures obtained.

The Spanish discoverers of America were men of marked ability, capable of enduring privations of every kind, prompt in action, prepared for every emergency, proud, brave and self-reliant to the verge of rashness, eager for adventures, cruel, unscrupulous, and rapacious, of unbounded greed and ambition. They sought and found gold and silver in Peru and Mexico in such quantities as they had never dreamed of; the new world brought to Spain greater wealth and glory than Columbus ever expected to find in Cathay or the Spice islands. Spain, it is said, drew from America during the sixteenth century seven hundred million dollars in gold and silver, a sum fully equal to ten times as much in purchasing power at that time as it would be today.

In the exploration of North America, the Spaniards took little interest. “What need have we,” they said, “of things which are common to all the countries of Europe—to the south, to the south for the great and exceeding riches of the equinoctial; they that seek riches must not go into the cold and frozen north.”

The French, though they made some remarkable journeys in the continent of North America, furnished but one discoverer whom we shall notice, Jacques Cartier, a French navigator who was appointed in 1534 by Francis I to the command of two ships for exploring the district near the fishing grounds of Newfoundland. He sailed up the Saint Lawrence and took possession of Canada for France, erecting a wooden cross with the inscription “Vive le Roy de France.” In 1541, a settlement was made near Quebec, the commencement of the French colonization in Canada.

The English were far behind the Spanish and Portuguese in the exploration of America. Their first great voyagers after the Cabots were slavers, buccaneers and pirates. Their most noted commanders were John Hawkins and Francis Drake, who carried a cargo of negro slaves from Africa to the West Indies and sold them at an enormous profit. They there heard of the Spanish galleons bearing the treasures of Peru and Mexico to Spain, and of the cruelties with which English seamen, taken prisoners, had been treated. On their return, fleets were equipped and sent to the Gulf of Mexico to capture the treasure ships and avenge the wrongs of the English sailors.

The queen frequently furnished ships belonging to the royal navy; they were equipped by Raleigh and other English noblemen, and the prizes were divided between the crew, officers, nobles, and queen, the queen obtaining the largest share. Sir Francis Drake, one of the boldest and most successful of these cruisers, on one trip overhauled and plundered over 200 vessels and pillaged towns and cities. Several times Philip II of Spain demanded his surrender as a pirate, for during all this time the two nations were at peace; the queen hesitated and delayed, but never yielded to the demand. There and then the foundation was laid of the navy and seamen of Great Britain.

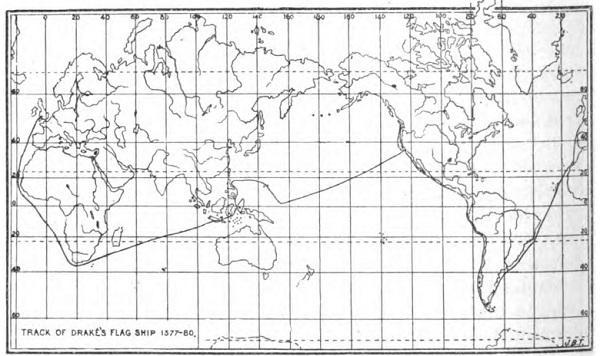

In 1577 Drake was summoned to a private audience with the queen, at which it was agreed that a fleet of five ships should be equipped, nominally for the Mediterranean but really for the South seas, as the Pacific Ocean was then called, to capture the great galleons, the treasure ships of Spain; and that the queen should contribute 1,000 crowns to the cost. On August 20, 1578, Drake, with this fleet, reached the Straits of Magellan and sailed through them in two weeks into the Pacific. There they encountered long and terrific storms, which carried them far south of the straits. One of Drake’s vessels had been broken up for firewood, another swamped in his sight, and the third deserted and returned to England.

On the fifty-third day of the tempest, Drake found himself south of Cape Horn, where no other vessel had ever sailed. Here, according to all the maps, was the great Austral continent, which extended an unbroken land area from the Straits of Magellan to the Antarctic pole; but he found only water—before him rolled the waters of the Atlantic and Pacific in one great flood. He walked to the end of the farthest island, lay down, and with his arms embraced the southernmost ground of the new world. Then the weather changed and all went well.

He sailed along the coast of South America, captured Valparaiso, took all the treasures he could find, refitted and provisioned his ships, and sailed northward, taking treasure ships and plundering cities until his vessel could carry no more, although it was ballasted with silver and gold.

FIGURE 2-Drake’s Circumnavigation.

Instead of returning as he had come, Drake determined to seek and find the fabulous strait so long sought by Columbus, and by that channel to find his way home. He followed the coast from Central America northward to the latitude of Vancouver and took possession of the land for England, calling it New Albion; then, finding the coast still trending to the northwestward and the weather growing more and more severe, he gave up his attempt, landed at the harbor of San Francisco, refitted his ships, and returned home by the Cape of Good Hope, reaching Plymouth in September, 1580, the second man to circumnavigate the world (figure 2*). What his reception would be at home was questionable. The news of his exploits had reached Spain the year before, and the ambassador of Philip demanded that he should be executed as a pirate, and renewed the demand as soon as he heard of the explorer’s return. The result of this demand was for some time doubtful; but when it was heard that a Spanish hostile fleet had landed on the Irish coast, the queen determined to support Drake and receive her share of the spoils. What they were we are not told, but they must have been very great as Drake’s share was 10,000 pounds, equal to $400,000 of our money today. This voyage of Drake completed the discovery of America from the northern coast of Labrador southward around Cape Horn and northward to 48°, the latitude of Vancouver island.

This is Part 3 of 4.

Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4

References:

- Hubbard, Gardiner Greene. Discoverers of America: Annual Address by the President, Hon. Gardiner G. Hubbard. National Geographic Society, 1893.